Intro

Two weeks ago, I took the PATH train to New Jersey with my boyfriend, and did something I hadn’t done for over eight months: I watched a movie in a theater. To be specific: The Uninvited (1944), at the Loew’s Jersey Theater. It was the experience economy, minus the economy: the Loew’s Jersey Theater is a 3,021-seat movie palace, which was constructed in 1929 and closed in 1986, before being resurrected as a volunteer-run non-profit in 1993. Sitting in the cavernous hall, with a ticket I paid $8 for, eating $1 popcorn served by an unpaid concessions worker, listening to the pre-show organist eke out Bach’s Toccata on an $80,000 restored pipe organ, and surrounded by about 100 people at most (that’s 3% occupancy, for the COVID capacity alarmists among us) all I could think was: this cannot possibly be profitable.

Ok, that wasn’t all I was thinking. I was also thinking about how much I missed movie theaters, and how grateful I was to be back in one, about the slow decline of theater audiences and the (arguable) concomitant decline of quality films in general, about when exactly people began restoring cultural artifacts like pipe organs (object restoration must be a somewhat recent practice?), about this essay by Roland Barthes called “Leaving the Movie Theater”, and just generally how strange and unmoored this year has been. But my top-of-crust consciousness was tallying audience members, estimating the cost of electricity, the cost of upkeep, of occupancy, of food, of time -- all in service of some imagined bottom line.

This is definitely a byproduct of having worked in finance for two years, and a (perhaps native?) tendency of mine to ricochet from the moment-at-hand into all of its possible offshoots and implications. Maybe it’s a byproduct of living a few hours of my week on Twitter (where we’re all accustomed to imagining every possible permutation of reaction to an idea before it's even been expressed). Or it’s a byproduct of the immediacy of single-click delivery, or ridesharing, or SVOD entertainment — and the way in which a hastening of physical supply chains are probably accelerating the velocity of thought itself. Or maybe I just inherently have a mercenary bent to my worldview -- with the “can this be profitable?” inquiry just the beginning of a whole other hierarchy of ingrained assumptions about what is important (plenty of people watch movies without wondering whether anyone is making money and that is honestly probably a much more satisfying way to live).

In other words, should I have even cared about whether someone was profiting from my presence?

Probably not. Watching film is theoretically an escape from all that. It was for me too: back when movie theaters were open in NYC, I’d see three or four films in a week -- and sometimes way more -- with pretty much no thought about who was making money from me. I recently stalked my past self on Letterboxd, and here’s a sample entry from the week of July 19th, 2019: A Faithful Man (Quad Cinema), North By Northwest (IFC); July 20th: Pickpocket and Au Hasard Balthazar (Anthology); July 21st: A Matter of Life and Death (Home); July 24th: Mamma Roma (Metrograph); July 25th: Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood (Village East); July 26th: The Mountain (IFC) (just missing the weekly cutoff: Life, and Nothing More…, Ugetsu, and Les Dames Du Bois de Boulogne). The venues: a mix of non-profit theaters, some independents, and IFC, which is owned by AMC Networks.

In that essay by Barthes I mentioned above, he describes beholding a film as a kind of act of hypnosis. But my favorite line from the work isn’t about film -- it’s about TV. Barthes writes that “television doomed us to the family”...which might sound like a misanthropic and unverifiable sociological diagnosis until you look at the statistics and accept he actually has a point (in 2018 the Bureau of Labor statistics found that 57.2% of Americans watched TV with family every day. Just 3.8% of Americans reported watching TV with friends).

Anyway, this brings me to the point of this piece, which is about what (I personally think) happens when we consign viewing to the home/family (especially as at home viewership has surged due to COVID). Onto the numbers baby...

Onto the numbers

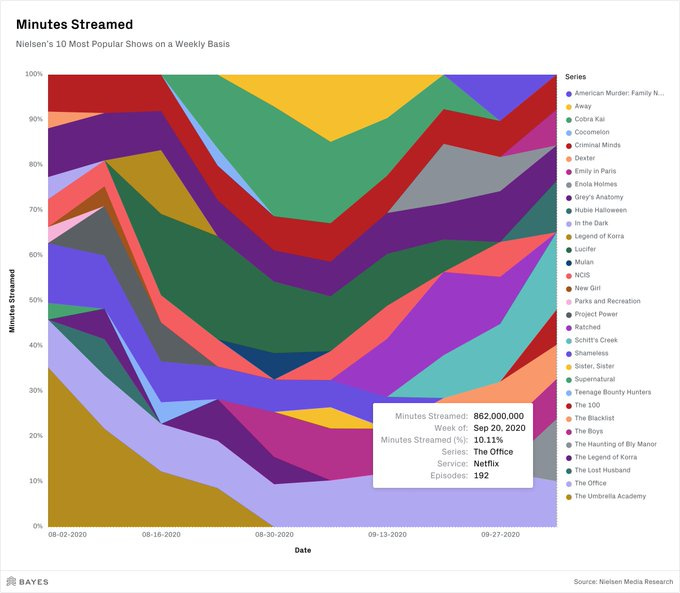

So Nielsen has recently (as of August 3rd 2020) started publishing the top 10 shows streamed online, organized by millions of minutes streamed. It’s dominated mostly by Netflix shows (both original and un-) and it's pretty staggering to think about. Here’s all of the current data displayed as an area graph (sadly there’s no way to embed the graph on Substack, but if you want to mouse over this as an interactive chart, here’s the link). Because the Nielsen data is released with a few weeks’ of lag, the data is current from August 3rd - October 11th. Note: the graph was made in collaboration with the team at Bayes a data visualization company founded by Justin Woodbridge and Will Strimling. If you like the work, you should contact them!

So there are a couple of interesting takeaways from the data — probably more than I can reasonably address in this post. For one, it’s pretty clear that the shows with ongoing popularity aren’t Netflix (or Amazon or Disney) originals -- they’re anchor shows like The Office, Grey’s Anatomy, and Criminal Minds, which all have many seasons, and embedded fan bases that date back to the mid-aughts (the film critic A.S. Hamrah once described the streaming strategy this way: “Successful multinational companies are gentrifiers: they move in on old content before they start to make their own content and become television networks”). Concocting a narrative for why this might be isn’t too difficult -- these are shows that were popular when they aired on networks (NBC, ABC, and CBS respectively), and can operate equally well as entertainment, ambient noise, or fodder for dating apps. They are shows that are comforting in their nostalgic capability and in their mass-market appeal. At their peak around 2009, Grey’s Anatomy and Criminal minds were the 10th and 11th most popular show in America — and given their placement in these Nielsen streaming rankings, it’s arguable that they’re even more popular today (perhaps giving more credence to the idea that we never left the aughts).

Another reason might come down to episode count: those three shows (The Office, Grey’s Anatomy, and Criminal Minds) all have 190+ episodes, which means that it takes a lot of time to work your way through a series (especially as the latter two shows are still on the air).

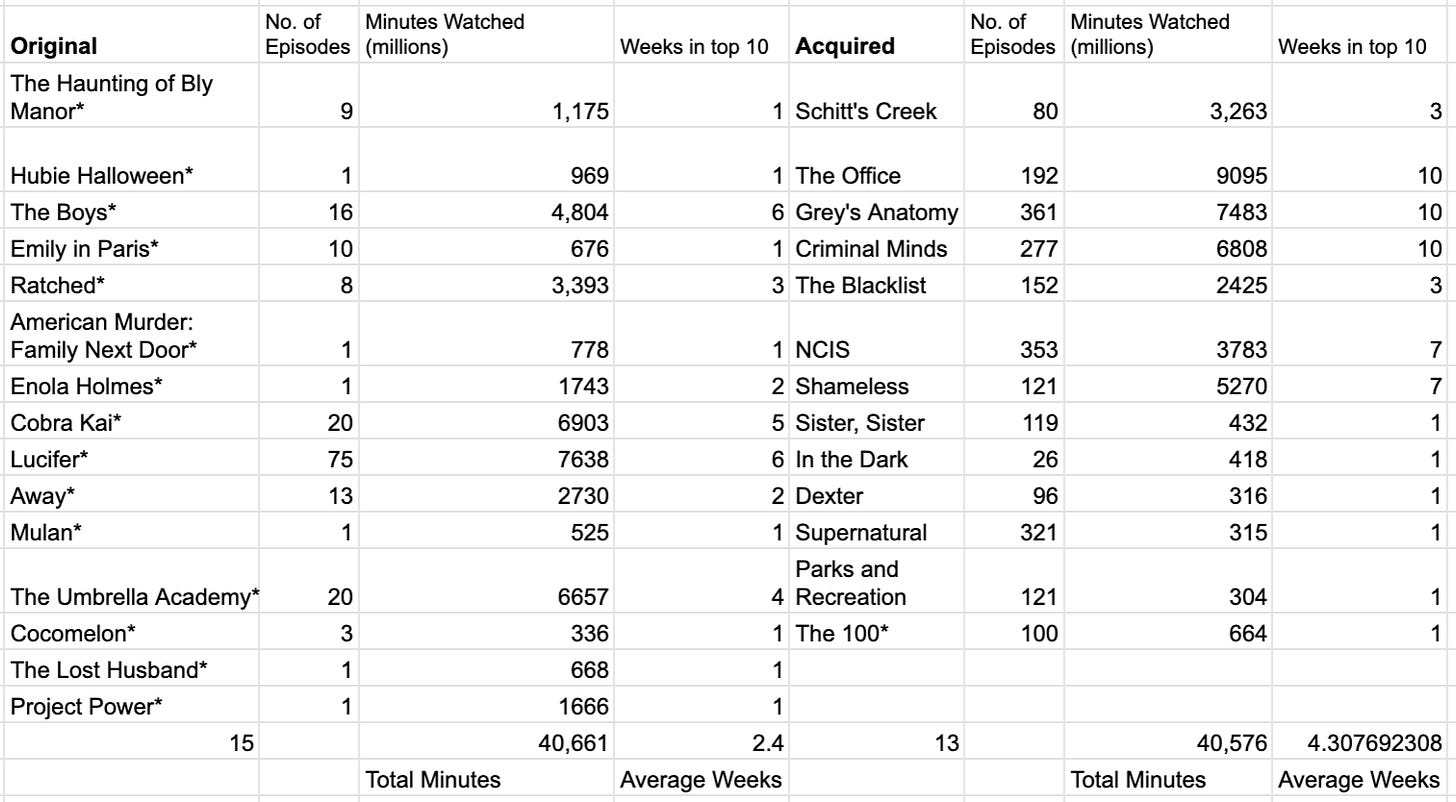

Here’s the data above represented in a spreadsheet. This is the ephemeral and fickle nature of an audience, in the form of a cold and empirical table. We see that Netflix shows (and they are mostly Netflix shows, with the exception of The Boys and Mulan) enjoy on average a little less time in the top 10, and about an equal number of total minutes viewed, despite being a little over-represented (15 vs 13 shows). Each category accounts for about 40 billion minutes cumulatively, or ~50% of the 81.2bn total.

The reasons for this are pretty obvious - again, there’s more back-catalogue for shows that enjoyed years of renewals and syndication. I think this chart also does a good job of illustrating what a lot of people lament when they talk about streaming: the popular original shows are often short-lived (or aren’t even shows: in the case of limited series like Ratched or The Haunting of Bly Manor) and cancelled for seemingly no reason.

I think this is the Netflix “sleep-as-competition” mandate (articulated by Reed Hastings) in full, illustrative force. When the imperative is to dominate your users’ time, it becomes increasingly irrelevant how that time is used, as long as it is spent consuming something in your rotation: novelty and “new content” increasingly trounces renewed shows (with the rare exception of a show like Emily in Paris…which was just renewed for a second season).

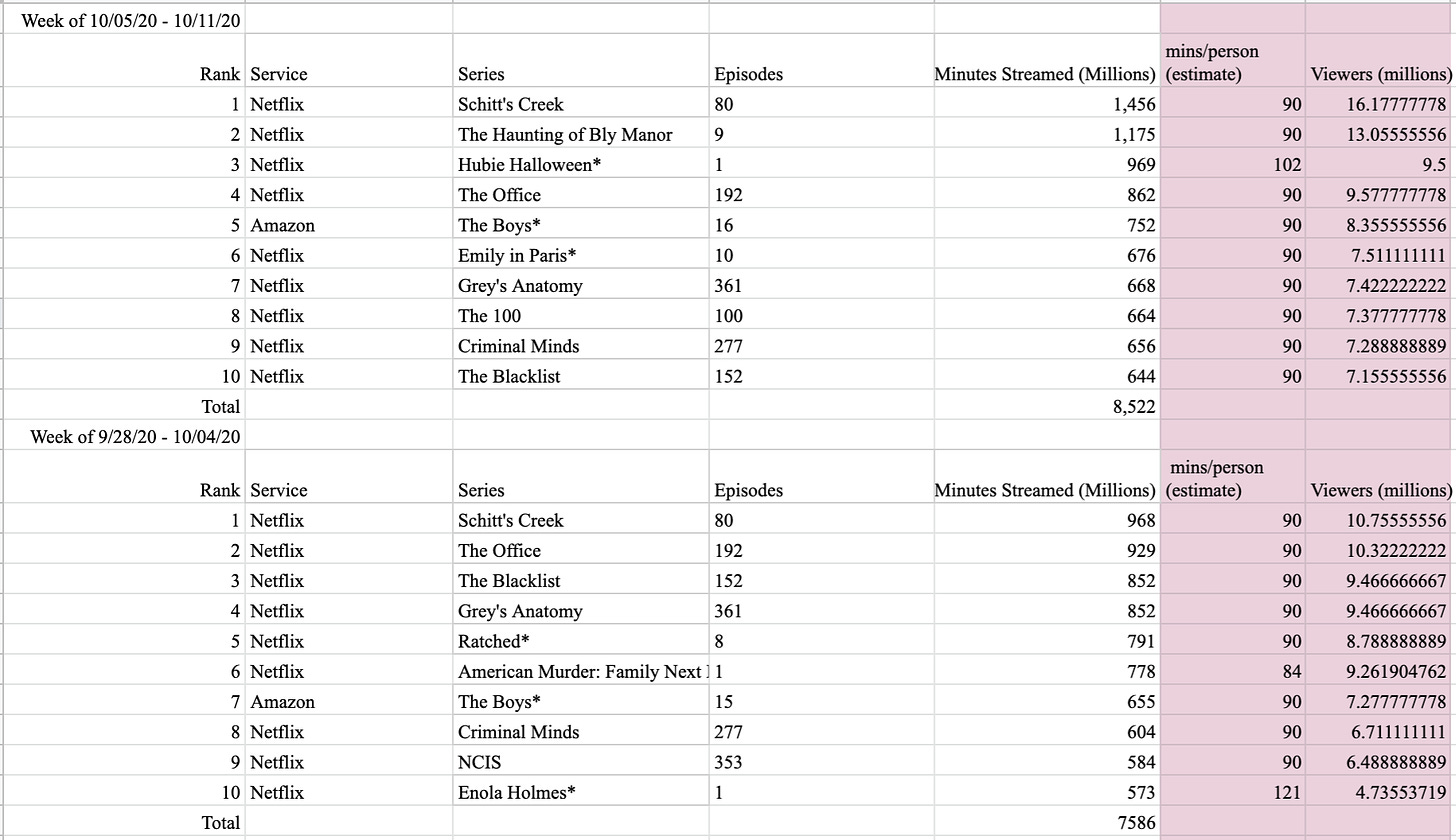

You might look at the charts above wonder — how do these “millions of minutes watched” convert into viewers? Nielsen tracks minutes, not people. This, in itself, is kind of a perfect encapsulation of the present moment. Time, not people, as the end-state of all measurement. In the world of analogue television and in film, producers are (or were) rewarded for outsize successes, either in the form of syndication fees (e.g. when you license your show after it hits 100 episodes) or in film financing where producers share in a movie’s profit. Those fees and profits usually have some kind of relationship to the number of viewers a show or film has. But in streaming, financial upside for production is usually capped (though some regions are trying to change this; Netflix, for example, just struck an agreement with German creators to pay out royalties for shows filmed in the region).

Netflix is comfortable operating at slimmer margins than networks and film studios did in their heyday, which is why they’ve been able to out-spend their rivals (who had gotten perhaps lazily accustomed to affiliate fees and ad revenues). Investors don’t care that Netflix operates at roughly 20% EBITDA margins, while most cable companies are around double that at ~30-40%…because the idea is that Netflix can outspend competitors, and doesn’t have to disentangle themselves from the affiliate fee/advertising-based model of legacy cable companies (that’s the very short version…the longer version is the hyperlink in the first sentence of this paragraph).

This means that winning, for Netflix, is less a matter of higher profits than it is a matter of triumphing in the realm of time, and how you personally choose to allocate it. While this has led to some good things (more shows means more opportunities for creatives), it also has led, I think (and I think a lot of other people think too), to an over-saturation of content.

Netflix (and all streaming) arguably marks the end result of what David Harvey identified as “time-space compression.” In his book The Condition of Postmodernity. Harvey writes:

the history of capitalism has been characterized by speed-up in the pace of life, while so overcoming spatial barriers that the world sometimes seems to collapse inwards upon us. The time taken to traverse space and the way we commonly represent that fact to ourselves are useful indicators of the kind of phenomena I have in mind. As space appears to shrink to a 'global village' of telecommunications and a 'spaceship earth' of economic and ecological interdependencies - to use just two familiar and everyday images - and as time horizons shorten to the point where the present is all there is (the world of the schizophrenic), so we have to learn how to cope with an overwhelming sense of compression of our spatial and temporal worlds.

I first encountered Harvey in college, while writing my history thesis on credit cards. But I think his observations work equally well when applied to the phenomenon of toggling through Netflix, confronted with a conveyor belt of shows you’ve never heard of (in other words: “time horizons shorten to the point where the present is all there is (the world of the schizophrenic)”). A shortened time horizon means that any week can be billions of minutes, so long as you have a medium of eyeballs to channel those minutes (humans are the medium, time is the message).

Either way, the chart above represents a little over 80 billion minutes of viewership in the span of ten weeks. How many people are 80 billion minutes?

It is kind of possible to estimate. Kind of. Let’s use Schitt’s Creek as our example, as it’s the top show for the most recent reported week. If people on average watched 90 minutes of Schitt’s Creek, that would come out to around 16 million weekly viewers. Edge that up to 180, and you get 8 million. If everyone who watched Schitt’s Creek allocated 100% of their weekly TV viewing time to the show, you might have something like 1.23 million viewers. Or if we went to the opposite extreme and assumed everyone watched 2 minutes of Schitt’s Creek (the way Netflix quantifies a view), then you’d have 728 million viewers (kind of unlikely, as Netflix has only 195mm worldwide subscribers). And so on. The only orienting clue we get is when a movie shows up -- a data point with a calming gravitational pull. Because we have Hubie Halloween in there (god bless you, Hubie Halloween), which is 102 minutes, we can organize these numbers with something approximating assurance (though, again, we actually kind of can’t). Anyway, things roughly fall into place from a viewership perspective when you designate 90 minutes as the average weekly viewing time (though that honestly seems low. But I digress.)

These may not be totally accurate estimates — but the display does make you wonder…if shows in the top ten are averaging in the low single-digits of users, what does the long tail of viewership look like on streaming services? After we drop off from 7 or 4 million viewers, how much further do we go? Which shows have 2 million viewers? Which have 1 million? 500,000? 100,000? 20,000?

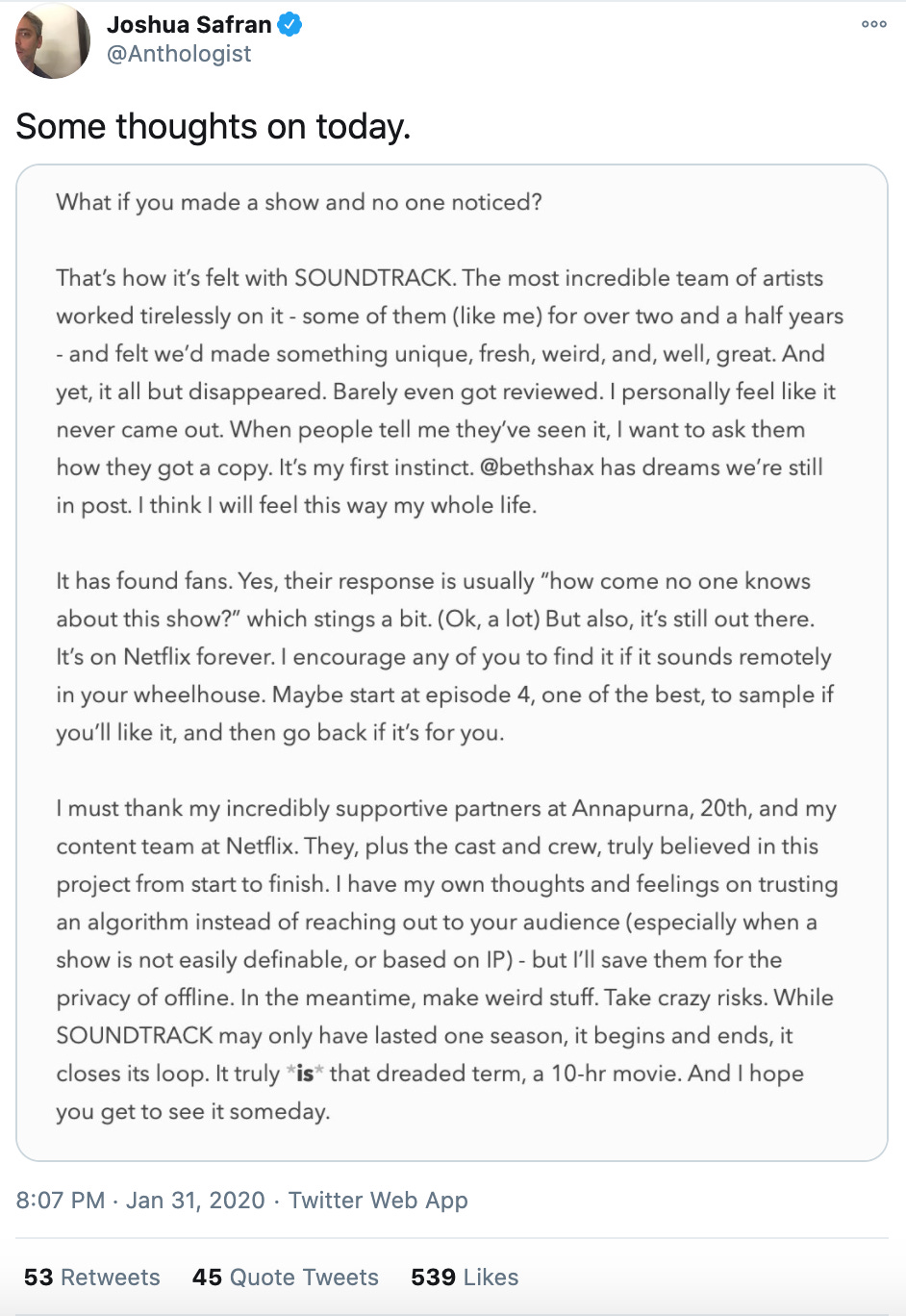

Maybe instead of trying to quantify that question, we should qualify it. A few months ago, I came across this Tweet from the creator of the Netflix show Soundtrack:

“What if you made a show and no one noticed?” I wonder how many producers of streaming shows feel the same way: months or years of preparation, hundreds of people enlisted to bring a vision to fruition, casting calls, days on set, arduous hours spent in post-production…only to find that the program you lovingly and carefully produced has landed in a cemetery before it even had a chance at life. It’s almost the opposite idea of Harvey’s “shortened time horizons” idea. Between writers, producers, actors, directors, crew members, editors, and marketers, five hundred people, or more may work on a show. Assuming everyone spends one year, and forty hour work weeks (a conservative estimate), you’re looking at roughly 115.2 million minutes. Admittedly that’s less time than the minutes spent streaming Enola Holmes the week of September 28th 2020. But the work was probably a little harder. And more importantly, the time is expanded, not compressed, across a horizon of a year or more.

Another way of looking at it: if 100,000 people watch one episode of that same 60 minute show (6 million minutes in total), that is just 5% of the amount of time it took to make the show in the first place. Maybe a bad-faith (and insulting) way of comparing/looking at time. But it does suggest a somewhat asymmetric relationship between input and output.

In 2010, there were 105 million cable subscribers, and a little more than 210 shows on the air. In 2020, there are roughly 84.5 million cable subscribers, 73 million Netflix subscribers in the US, and over 530 shows on the air. This means that the odds of being a runaway, Queen Gambit-esque hit are slimmer than ever. Sure, there were tons of failed shows in the analogue TV era as well — but there was less competition. For a person working in TV today, I do wonder what upside means? Maybe I’m overthinking it — in an era where making it as a creative person is more difficult than ever, maybe being paid to do what you love is the upside in itself, and the proliferation of new shows just represents more opportunity (and because having a runaway success is so much rarer, the pressure to have one is diminished, which means that saying/doing what you want — if you’re given the right budget — is the reward in itself).

Part of the mystery of all of this is in that original Barthes quote: the idea that TV “doomed us to the family.” Another, less pessimistic way of saying this is: TV made it impossible to know what anyone beyond our bubble was watching or enjoying. Yes, we have Nielsen. Yes we have Twitter. Yes we have reviews. But the feeling of synchronous, collective effervescence with strangers? That’s only possible in one place. The movie theater.

Just two more minutes of your time?

I’m not in denial about the state of moviegoing in America. Even before the pandemic, cinema attendance was falling precipitously. Even before Netflix offered streaming, people weren’t exactly raring to go to the cinema: in 2006, 75% of Americans said they preferred watching films at home. I’m in the minority, and I accept it.

Interestingly, film is a kind of referendum on the Harvey-ist conception of space and time. Yes, the act of beholding a film is a compression of space (you are flung into another world, another image) and time (see Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time). But from an economic perspective, film is about as rooted in space and time as you can get. You go to a theater, you pay for your ticket, you sit down, you watch you leave the movie theater — and the money you spent is split between the cinema and the producers. If you know how much a film earned, you can guess approximately how many people watched it. And likewise (barring walk-outs), you also know exactly how much time they spent watching. It’s a world away from the quantification of streaming.

But let’s return to the aesthetic and social pleasure of seeing a movie in a theater. In the words of Barthes, film also resolves the more ineffable mystery of other people, how they view, and what they like:

What does the “darkness” of cinema mean? (Whenever I hear the word cinema, I can’t help thinking hall, rather than film.) Not only is the dark the very substance of reverie (in the pre-hypnoid meaning of the term); it is also the “color” of a diffused eroticism; by its human condensation, by its absence of worldliness (contrary to the cultural appearance that has to be put in at any “legitimate theater”), by the relaxation of postures (how many members of the cinema audience slide down into their seats as if into a bed, coats or feet thrown over the row in front!), the movie house (ordinary model) is a site of availability (even more than cruising), the inoccupation of bodies, which best defines modern eroticism – not that of advertising or strip-tease, but that of the big city. It is in this urban dark that the body’s freedom is generated; this invisible work of possible affects emerges from a veritable cinematographic cocoon; the movie spectator could easily appropriate the silkworm’s motto: Inclusum labor illustrat; it is because I am enclosed that I work and glow with all my desire.

And it also brings us closer to resolving the greater mysteries of existence. In Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky wrote that cinema allows us to be:

a participant in the process of discovering life, unsupported by ready-made deductions....going beyond the limitations of coherent logic, and [beholding] the deep complexity and truth of the impalpable connections and hidden phenomena of life.

This is something that I think television, or at-home viewing (with its constant distractions, screen-toggling, phone notifications, etc) can’t ever accomplish. To re-use that Harvey quote again: “time horizons shorten to the point where the present is all there is (the world of the schizophrenic).” The proliferation of television (over 500 vs ~200 ten years ago) has arguably rendered daily life a little more unknowable.

Coda:

Ok I do think it’s pretty interesting that, on January 21st, 2020, Netflix announced they were redefining “view” from watching 70% of an episode to watching the first two minutes of an episode.

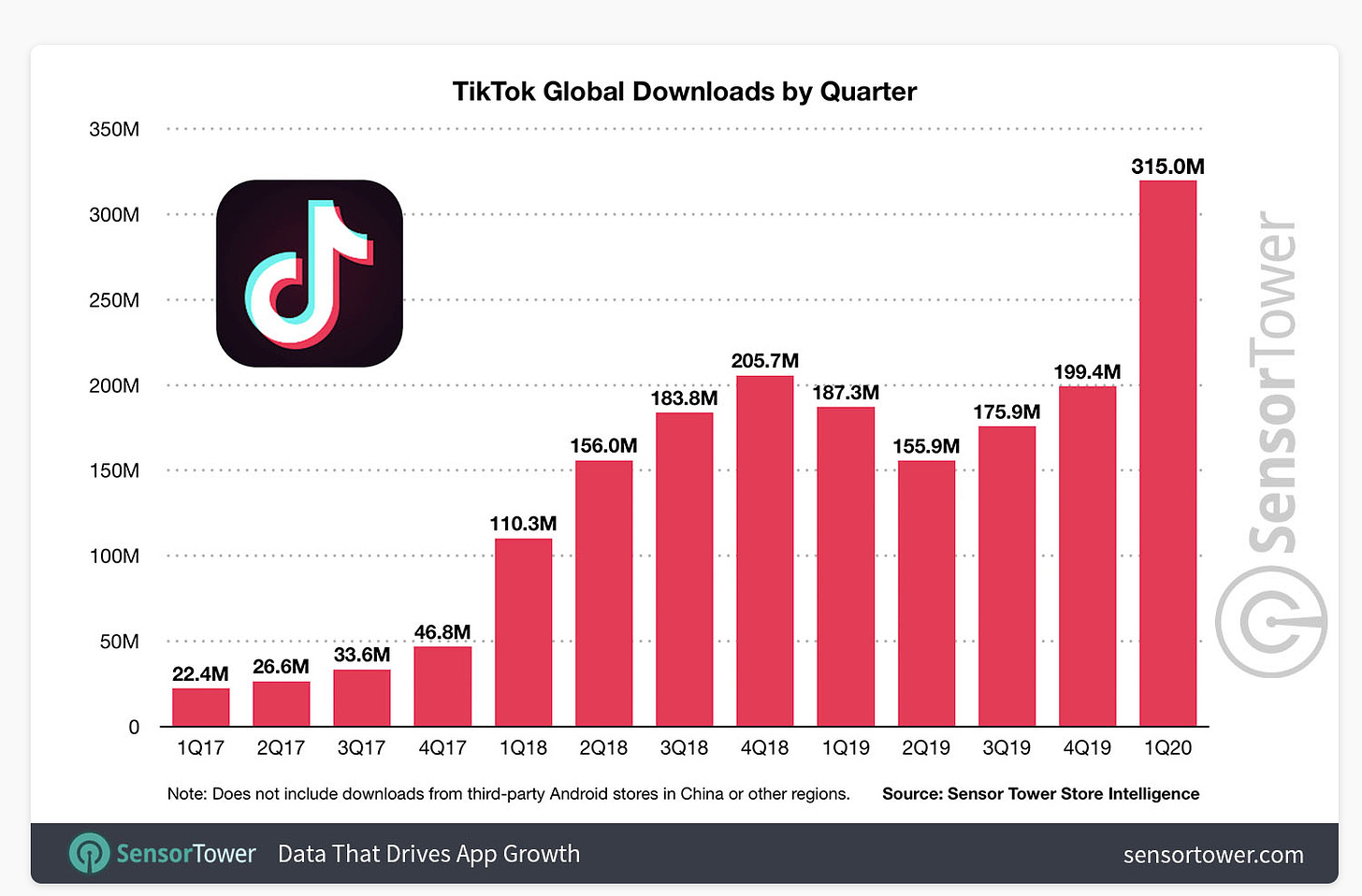

Could they have been sensing a seismic shift in the way people chose to view content? Here’s an interesting chart: notice that the surge in TikTok downloads coincides with the Netflix announcement:

TikTok now has over 850 million users — I have not yet seen anyone try to quantify the billion of minutes viewed/week that converts into, but it’s quite likely that it dwarfs Netflix’s weekly minute view count (which has 195mm users).

In the words of David Harvey: the time horizon is shortening, the present is all there…

If you’d like to get in touch, my Twitter is @VirtualElena and my email is elena96b@gmail.com

I'm glad I've found this, as I was thinking about this idea this week, and I started to begin thinking about it from first principles.

I also listened to a podcast that discusses the viewership stats within Netflix - I think they claim that the stats are intentionally concealed such that they will have favourable bargaining power with their creatives/producers/etc.

Podcast: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4NjdiNoGvvpAyAASqQWGuW?

"...that is just 5% of the amount of time it took to make the show in the first place"

This has always been true. It takes a lot less time to read a novel than it does to write one. Maybe even in aggregate, the total time spent reading a book might not equal the time put into creating it. Likewise for most films even in the pre-streaming era. Creativity is hard. Consumption is easy.