The Refrain

One of the most persistent refrains of the COVID era is that lockdown accelerated the world’s shift to eCommerce. The indelible, seemingly divinely-ordained pull-forward. In the beginning were the words: COVID dramatically accelerated eCommerce penetration. The shift to eCommerce is pulled forward by 5 years. No, 10 years in eight weeks. Then the trickle of quarterly earnings arrived with the numbers to validate the prognostications of sell-side analysts and management consultants everywhere. Amazon (retail, ex-cloud) and Shopify both grew more in absolute dollar terms than Walmart did during the second & third quarters of the year (Amazon revenue +$47bn, Shopify GMV +$32.4bn, Walmart revenue +$14.2bn). Major retailers like Lululemon and Nike saw an increasing amount of their revenue derived from online sales (Lululemon averaged roughly 50-60% of revenue from eCommerce vs 29% last year; Nike averaged 30%). People tried grocery delivery for the first time. Online crushed physical, once and for all.

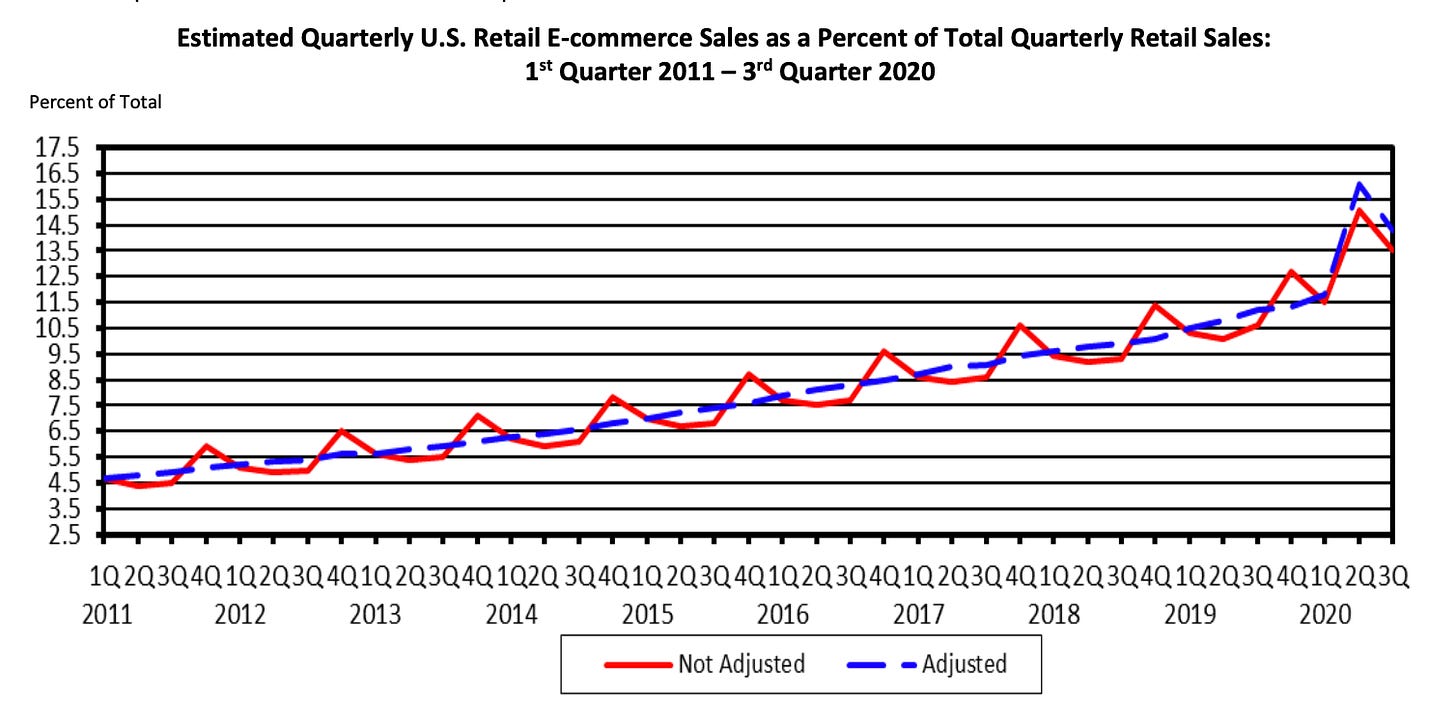

But zooming out paints a different, less teleological, not quite so meteoric picture. Per the US Census Bureau, in Q3 of 2020, online sales were...just 14.3% of total retail sales -- admittedly up 30% from last year, but down from their height of ~16.1% of sales in Q2.

Put another way...if your memory of the past year was erased, and I told you that a pandemic would rip across the world, rendering us all loyal supplicants to online shopping, what percent of sales would you assume eCommerce would be of overall consumption? Probably pretty high, right? I posed the question to some family and friends, and everyone guessed in the 50-80% range. The reality -- a little over 14% of sales -- is actually shocking. The takeaway shouldn’t be “eCommerce is eating the world” it should be “despite lockdown, store closures, mass layoffs, and global logistics networks that rival militaries in terms of sophistication, eCommerce was less than 1/6th of sales in the US.”

Intelligence, for the moment, is outpacing life.

This past weekend I went back and skimmed some of the sell-side reports that filled my inbox during the outset of the pandemic. The thrum of emails hit their stride in the first week of April (reflecting the one-week lag in credit card data). I began seeing headlines like “Not business as usual: eCommerce growth accelerates in third week of March” with revelations like: “Grocery & sporting goods strong. Best performing categories include: Online Grocery (up 41% in March from 3/1 to 3/24, 24pts higher than Feb at +17% Y/Y); Sporting Goods (up 32% Y/Y in March, 33pts higher than February at -1% Y/Y)” A few weeks later: “US eCommerce growth through April was +63% Y/Y, up 38pts from 24% growth for March, and up from 57% Y/Y growth at the time of our last update (through 4/23).” Later: “Weekly growth for the week ending 5/29 remained at its recent high of +85% y/y, unchanged from the week ending 5/23, despite more of the US opening.” And so on.

Fast forward to the end of the year, and you see a chart that looks like this:

The point of including this is to put us all in the mindset of...me, or anyone working in finance & tech, probably living in a mental future that far outpaces the physical present. The pandemic partially seemed like an opportunity to corroborate the promises we’d been hearing for years (or at least, I’d been hearing for 2 years, and started attending “Future of Retail”-themed conferences hosted by investment banks). The buzzwords were finally being crash-tested. BOPIS transitioned overnight from a retail conjugal visit to the only way we could fathom picking up groceries, clothes, and 65 inch TV sets. Target added 10 million digital customers in the first half of the year and Walmart doubled their eCommerce sales. Still, despite all of this, online sales were just 16.1% of the overall total at their peak in the second quarter of the year.

I’ve been struggling with squaring the mental anticipation with the physical reality. I think the takeaway from the pandemic is that there is a massive asymmetry in the power, vision, and will between technology/engineering/logistics, the government, and human volition. Just compare Amazon’s early response to the pandemic to the government’s:

Amazon announced two-weeks paid leave for any employee diagnosed with COVID-19, in addition to unlimited time off for hourly employees through the end of April (March 11)

Announced the hiring of 100k more Amazon workers (then upped to 175k), and $2/hr increase (March 16th)

Stopped accepting non-essential items in Amazon warehouses from 3p sellers (March 17)

CARES Act passed (March 27th)

And….the CDC recommends mask-wearing (April 3rd)

We all at some level (either actively or subconsciously) understand the militaristic precision that Amazon and pretty much any vertically integrated retailer can offer (Amazon’s head of logistics is literally nicknamed The Sniper). And I think this understanding (both active and subconscious) exerts a kind of overpowering, psychological hegemony (call it eCommerce-as-a-vibe) that renders us less able to acknowledge one simple fact: shopping in person is still more popular than shopping online.

Of course, part of the difficulty of making sense of physical retail is that everything is shifting so quickly. A few months ago, Yelp found that 30,374 retail businesses in the US closed during the pandemic; (163,735 businesses closed in total, per Yelp). In New York City alone 1,000 chain store locations closed -- a 13.3% decline -- and by the end of September, 11,200 businesses overall closed in New York City (7,200 permanently). In LA, 15,000 businesses closed; in San Fransisco 6,200 closed. The understanding seems to be that big box retailers like Walmart and Target are the major brick and mortar beneficiaries, and that mom and pops are screwed.

But I also wonder whether this understanding is influenced by the fact that a lot of people who work in tech, finance, and media also happen to live in New York and California -- where retail has arguably fared the worst. Just look at retail job recovery as an illustration: in December, US retail jobs were back to 97% of their pre-COVID levels. But numbers were lower in NYC (87%) and SF (94%, where numbers have been drifting slowly downward for the past 5 years anyway). But it goes beyond jobs -- New York and California have the most expensive commercial real estate in the country as well. And while real estate leases are coming down markedly (in NYC they’re down 12.6% from last year), ground-floor vacancies in the 16 most popular shopping corridors of NYC are 20% higher, at 254 storefronts. Astoundingly, NYC’s Department of Small Business Services doesn’t even know how many retail storefronts the city has, let alone how many are vacant in total, so getting a fuller picture beyond the most popular shopping areas is a little more difficult. But gonzo reporting tells a similarly bleak story: a reporter from the local paper Patch walked along Second Avenue between 60th and 90th street, and counted 66 empty storefronts.

So just restating the mental backdrop: people in tech, finance, and media are primed to anticipate the downfall of retail because they live in cities that play host to some of the most visible disruptions in retail. Now to be clear, I’m aware that these ruptures are happening everywhere. I’m not going to convince anyone who prefers buying their Rick Owens t-shirts from Mr. Porter over Totokaelo (which, I just discovered in the process of writing this, is already gone) that physical retail is any more efficient or neat than the messy process of wandering, touching, and discovering. I’m not going to convince anyone that masking up and going to the corner deli is more hygienic or seamless than getting groceries from Instacart. But I love shopping in person (even for something as banal as canned soup or gum), and I think millions of people still do too. I have yet to find a form of “social commerce” as satisfying as wandering through the Lower East Side with my friends. I earnestly think the 60,000-SKU grocery store is a miracle that warrants celebration. Not to get all BLS-y, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics did release a study in 2019 that found people who shopped spent an average of 1.7 hours doing so every day. So rather than assuming retail has a foreclosed future (and perhaps rendering that just through sheer force of anticipation) what are some alternatives?

A Very Brief Historical Interlude (or...thinking about Architecture as Technology...or “the most profound technologies are those that disappear.”)

In 1919, the Abraham & Strauss Department Store in Brooklyn became the first retailer to introduce air conditioning to their stores. The technology (and it really was seen as technology at the time) had been teased and tested in the New York Stock Exchange (1902), the Missouri World’s Fair (1904), factories, and movie theaters (the first air conditioning system in a theater was installed in 1917--by 1938, 15,000 of the country’s 16,251 movie theaters were air-conditioned). But shopping wasn’t far behind. While we now think of air-conditioning as an immutable fact of life, the ability to cool air and control the temperature of an environment was at the time, radical.

Air conditioning unleashed a multitude of possibilities in the realm of shopping. The engineer Willis Carrier (of Carrier renown), advanced the idea that human comfort can be directly linked to temperature and humidity and was instrumental in convincing retailers to introduce air conditioning to their shops. This in turn dramatically shaped the aesthetics of shopping space. For one--it essentially made windowless department stores and cavernous malls a reality. In 1938, a writer for the trade publication Department Store Economist remarked that air conditioning enabled a selling space “free from the slightest daylight or natural ventilation and a more uniform, pleasing artificial lighting result...In many ways the elimination of windows adds to the beauty and selling efficiency of the store.”. Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the modern-day shopping mall, knew that he needed to include air conditioning in his first mall in Minneapolis (constructed in 1956). Gruen said “Whenever I got [to Minnesota] it was either freezing cold…or it was unbearably hot. From these personal experiences, under which I suffered greatly…I concluded that open public pedestrian areas in a climate of extremes…could not be a total success. So I carefully prepared the Dayton’s [Gruen’s clients] for the shocking idea of establishing completely weather-protected, covered and climatized public areas.”

Shopping malls helped proliferate yet another feat of engineering: the escalator (or perhaps it’s just as true the other way around: escalators helped proliferate malls). While the technology actually had earlier buy-in from retailers (Harrod’s installed the first escalator in 1898), malls in the United States represented a new storming ground— From the Harvard Design School:

1945–58: Marketing. Back in the West, the momentary lapse in consumerism caused by World War II gives way to an unprecedented and uninhibited inventiveness fueled by consumerism. Advertisers claim technology as the guarantee for economic success, and the Otis Company discovers marketing. Even though the basic idea of the escalator has remained virtually unchanged since its first application, it is heralded as a technology critical to the postwar prosperity. A direct equation between a building’s cash flow and number of visitors is formulated: maximum circulation = maximum sales volume. Store area is calculated in direct relationship to volume and flow of shoppers. Stores are now devised according to the equation, retail area above ground floor / capacity of the stairways < 1/20. That is, to carry one person an hour to every twenty square feet of merchandise area above the ground floor is to accomplish maximum dollar volume. The escalator can move five to eight thousand potential shoppers an hour, yet the sixteen hundred escalators in operation in the United States in the late 1940s are hardly enough to sustain the postwar shopping euphoria.

Technology is diffused not just through self-evident usefulness, but by self-conscious promotion. Recall the rather ominous quote in the Carrier advertisement from 1930 above: “Buildings still in blue print may be obsolete…Unless they plan to manufacture their own weather…[Manufactured Weather] will prolong the time during which the building will command profitable rentals and hold desirable tenants.” The Carrier ad is just one example within a coordinated pro-AC marketing blitz. In 1941, Chrysler hosted a conference titled “How Air Conditioning Builds Business Profits” with arguments that AC “Reduces lost time on account of illness”, “Improves employee appearance” and “Keeps Merchandise Clean.” The conference also closed with an anecdote claiming that “during one particular hot spell in Pittsburgh…Boggs & Buhl had 14 faintings among customers and over 20 among sales girls. A competitor [with] air conditioning…corrected this problem by 90%.” You kind of have to wonder about the 10% of fainting spells that persisted…but the point is that the introduction of air-conditioning in the US was largely a top-down effort:

The post-WWII success of AC was, however, less a matter of consumer approval and more a result of how “architects and builders made the decision to air-condition American homes and offices, then lenders and regulators stamped the change with institutional approval”. Although ideas, promotion, and marketing played key roles in the growth of AC, the triumph of air conditioning in the 1950s was based upon its integration into building design, construction and financing. Architects, builders, and bankers accepted air conditioning first, and consumers were faced with a fait accompli that they had merely to ratify. Advertising specifically helped in “domesticating and normalizing the use of technologies that might at first seem frightening… also ultimately marginalizing those who still refuse[d] to use them.” Domestic Air Conditioning.

In the pre-internet era, engineers had to figure out how to reconfigure space to support a critical mass of people; if you could figure out how to attract people to your stores, or manipulate the flow of shoppers (“maximum circulation = maximum sales volume” per the wisdom of the escalator manufacturers) you could manage profitability. Because technology made the relationship between the consumer and consumerism more convenient, and because its acceptance was relatively uncontested, shopping itself sponsored the complete alteration of urban and suburban sprawl. By the end of the 20th century, shops outnumbered churches, synagogues, and temples by 3.6 times, primary and secondary schools by 14.6 times, libraries by 25.2 times, and museums by 242.1 times.

In that period, engineering solved the rather unwieldy problem of “how do we bring an unfathomably large number of people together so they can shop, and justify the millions of dollars we just spent building out this department store or mall.” While developers had other tools to ensure profits (mall operators used a 1954 tax change to accelerate their depreciation schedules and, in turn, realize higher tax write-offs) this is something really worth highlighting. Bringing people together, in person, was just as much an engineering endeavor as it was an architectural, aesthetic, or ideological one.

Yes, there’s been a physical retail apocalypse, but that hasn’t been accompanied by a decline in physical retail sales. In the past five years, physical retail sales have increased by ~14%, despite tens of thousands of store closures in that period. In other words, the rise of eCommerce has likely coincided with — but not caused — the reckoning in over-retailing. It makes me wonder whether eCommerce is actually the enemy of physical retail — as we’ve long been primed to think — or whether the enemy of physical retail was the fact that there was just too much of it to begin with.

“We are over-retailed,” says Ronald Friedman, a partner at Marcum LLP, which researches consumer trends. There is an estimated 26 sq. ft. of retail for every person in the U.S., compared with about 2.5 sq. ft. per capita in Europe. Roughly 60% of Macy’s stores slated to close are within 10 miles of another Macy’s. - Why the Death of Malls Is About More Than Shopping, Time Magazine

Put another way, eCommerce might not be killing physical retail, it is killing the sprawl of physical retail. And this is a slow death, one that long pre-dated eCommerce. From an article in Fortune, circa 1995:

Among the economic victims of the new do-it-yourself movement are many of the old-style regional shopping malls that dot America's suburban landscape. The assiduously self-reliant have less and less use for these full-price retail centers, and their preferences are having an impact. In a recent survey by consulting firm Kurt Salmon Associates of Atlanta, 38% of respondents said they planned to shop at malls less often this year than they had in the past. The end result will probably be a big-time shakeout. The experts say that over the next few years, as many as 300 of the roughly 1,800 regional and super-regional malls--those with over 400,000 square feet of space--will be either shut down or converted to the warehouse-style retailing that do-it-yourselfers favor. Says Carl Steidtmann, director of research at Management Horizons, a retail consulting division of Price Waterhouse: "Regional malls clearly have a life cycle, and a lot of them are in their last throes."

In a way, the consolidation of retail is just a reflection and enabler of the way many people like to gather — in densely packed, often chaotic networks that favor serendipity and discovery. Cities do this naturally, malls did this forcefully. Victor Gruen envisioned the shopping mall as a way to graft the experience of the city onto the suburban core, predicting that large malls would become “urban sub-centers” in suburban space. The only thing Gruen and other mall retailers miscalculated was the number of malls actually required to sustain this. You might be able to argue that the consolidation of malls and department stores is now accelerating the process of urbanizing suburban America — we are coercing space into bringing us closer together. Jane Jacobs wrote about the way in which the kind of serendipitous contact found in cities (or perhaps, “urban sub-centers” of suburbia) imbues daily life with enigmatic substance:

“The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts. It grows out of people stopping by at the bar for a beer, getting advice from the grocer and giving advice to the newsstand man, comparing opinions with other customers at the bakery and nodding hello to the two boys drinking pop on the stoop….utterly trivial but the sum is not trivial at all. The sum of such casual, public contact at a local level—most of it fortuitous, most of it associated with errands—is a feeling for the public identity of people, a web of public respect and trust, and a resource in time of personal or neighborhood need…The absence of this trust is a disaster to a city street. Its cultivation cannot be institutionalized.” - Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

It might sound regressive, decadent, or even docile to view shopping as a vital form of public life. But honestly, this is America, and Americans love to shop. eCommerce may be reorganizing the world (and software is decidedly eating it) — but how do we help physical retail preserve its function as the country’s social lubricant (or if we don’t want private companies to continue subsidizing public life, as they’ve done for over a century, what are the alternatives?). It’s quite likely that the same energy directed toward orchestrating physical retail in the 20th century is now being channelled into making eCommerce as harmonious and efficient as possible. While there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, I wonder whether that process is also confining innovation to warehouses, user interfaces, and getting people to click on Facebook ads. As the history of AC and escalators indicate, every social phenomenon needs a self-aware technology to enable it. When does physical retail become self-aware again?

Threading It All Together

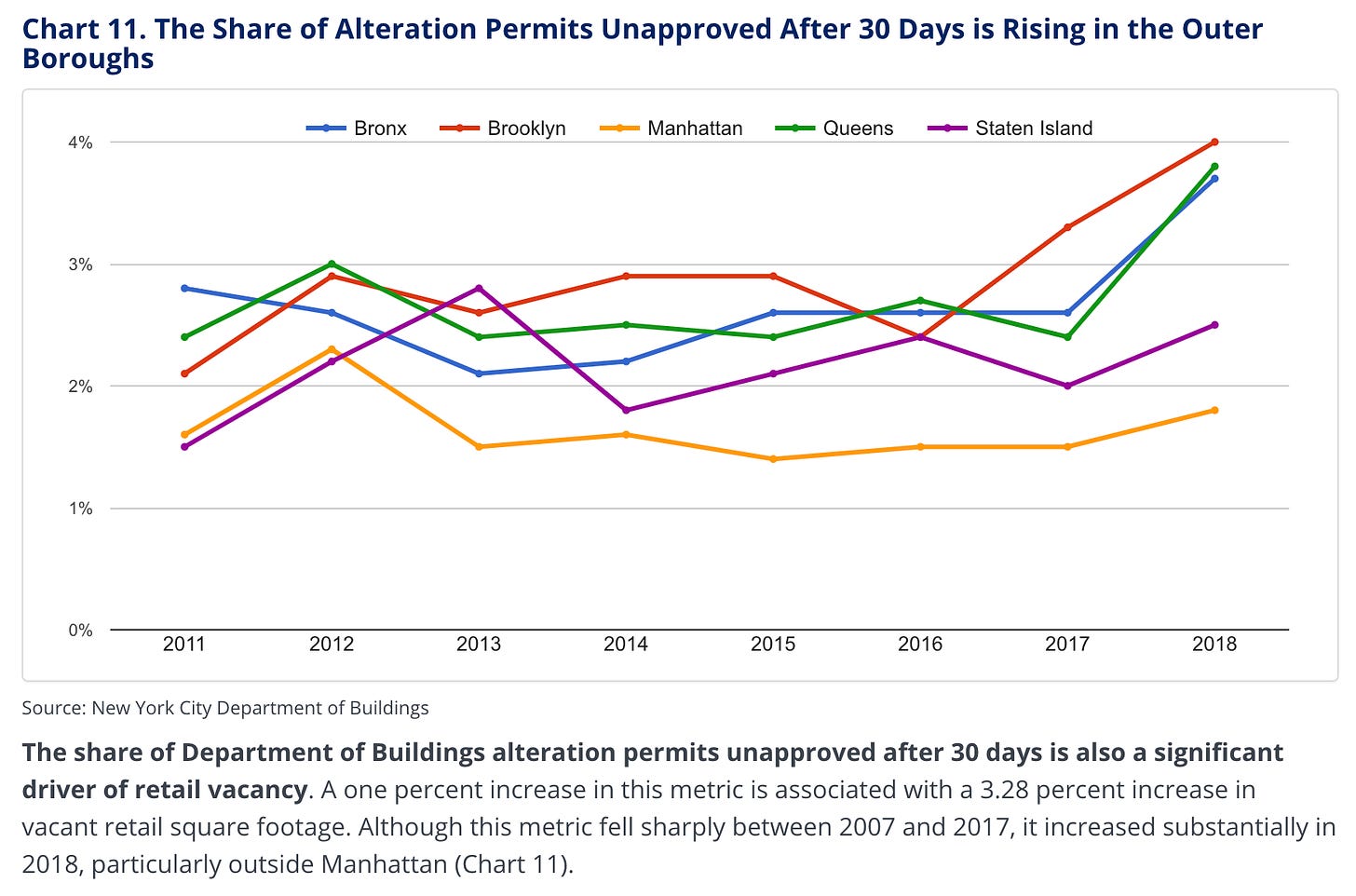

In 2019, the New York Comptroller’s office issued a study on the rise of empty retail space in the city. While the study found that Amazon drove vacant square footage higher by roughly 1% from the period of 2007 to 2017, the far more powerful driver of retail vacancies were actually…delayed government permits.

For every 1% increase in the number of building alternation permits unapproved after 30 days, vacant retail square footage increased by 3.28%. It seems like getting caught in whatever bureaucratic rigamarole governs the Department of Buildings had a far bigger impact on retail vacancies than Amazon did. Landlords had a massive impact too: retail rents rose by 22 percent on average citywide between 2007 and 2017, with a one percent increase in average retail rents associated with 0.33 percent increase in vacant retail square footage. As I said in my introduction, there are now thousands of vacancies in the New York City metro area alone. In the short term-these vacancies are caused by COVID, but if they persist in the long-term it will be attributable to exogenous factors like bureaucratic delays and landlord greed. Yet mentally, we’ll attribute those vacancies to lack of demand or eCommerce. My fear is that living in what looks like the death of physical retail, will expedite the actual death of retail. The tendency to mentally accelerate into the future has the potential to overextend things toward extinction.

The illusion of death of course, necessitates a will and testament. In his critique of contemporary urbanism, Junkspace, the architect Rem Koolhaas paints a picture of the miasmic ways in which planners aim to repurpose space once it appears unusable:

Junkspace expands with the economy but its footprint cannot contract-when it is no longer needed, it thins. Because of its tenuous viability, Junkspace has to swallow more and more program to survive; soon, we will be able to do anything anywhere. We will have conquered place. At the end of Junkspace, the Universal? Through Junkspace, old aura is transfused with new luster to spawn sudden commercial viability: Barcelona amalgamated with the Olympics, Bilbao with the Guggenheim, Forty-second Street with Disney.

Koolhaas is castigating a much broader trend in corporate, municipal, and institutional initiatives that (in an effort to make use of excess space) impose a cloying cultural uniformity over everything. Within retail, this trend is most apparent whenever someone talks about engineering physical space to function more like the internet. I’ve recently read pieces that posit physical retail as a form of “sponsored content” with the idea that a storefront is just a bit of targeted advertising, meant to entice you to make a purchase online. I’d imagine that if you design a space to function that way, you’ll be successful (you might even bring a space to a terminal apotheosis, and graft literal advertisements over vast refrigeration units, like you’ll find at some Duane Reade locations in the city). The effort to rebrand “space” as “marketing” is less a symptom of needing more advertising, and more a concession that we built too much space (again, this might be true of suburban malls, but it seems less accurate when talking about physical retail in cities). To physically de-densify would be an admission of failure or defeat. So we de-densify the content of space instead. “Please look, but don’t touch.”

Commercial and visual innovation increasingly feels like it lives on the internet. People can create low-overhead businesses and reach customers quickly (think Amazon’s 3p sellers, Stripe, Shopify, Facebook/Instagram Ads) and are relieved of the need to ever achieve the kind of physical scale required of retailers in the past. Tools and software like Figma, Spline, Unity, and Unreal make it possible to easily create not just new user interfaces, products, and games, but worlds with their own logic and economies. While the drop-shippers of eCommerce will probably stay confined to the web forever, I wonder why we don’t see more businesses that started on the internet breaching into the real world. Yes, you’ll find a stray Allbirds or Bonobos in the wild (the digitally native brand repatriated to the concrete jungle or local Westfield)…but those brands aren’t from the internet, so much as they used the internet to perpetuate popular demand.

What I’m looking for is something slightly different. Call it brand populism. Call it net nativism. Call it making retail space as idiosyncratic, surprising, and weird as the 3am discoveries you find in an Instagram wormhole. There are hundreds of thousands of shops that exist only online (some examples: Happy99, blum, and vewn which is managed by an animator with almost 750k followers on Youtube). Why don’t we get to wander inside of these brands in reality? The problems I explored above might be some of the bottlenecks (sclerotic governments, high rents), but there is also an unavoidable reality: the internet is simply a much more hospitable host to innovation and creativity than the physical world.

Maybe this will change soon — Shopify, for example, is hiring a “Spaces Lead” which could signal a move to give some of their small merchants a storefront. So the start might be a Shopify-hosted physical retail space. But this will likely be an early step toward what I’d like to see: a much more contiguous and rational relationship between the capabilities of internet and physical space. What would happen if we designed space as a way to mediate the flow of information online? How does physical space get rethought, knowing the astonishing capabilities and speed of a modern logistics network? As my friend Reggie likes to say, bits reorganized atoms. In the post-mobile, post-software-ate-the-world-and-now-we’re-in-the-microbiome society, what kind of spaces get built? And whose responsibility is it to think through these things? Does the onus rest with architects? With designers? With brands? With developers (of the software and real estate variety)? With investors? With, god forbid, the government?

Honestly, I don’t have the answer to these questions. Part of why I wrote this piece is to work through my thoughts and feelings about this period of time — a period when it took a pandemic to propel us into an eCommerce future we had long imagined for ourselves. Yes, we all now appreciate the convenience of online shopping. But I think we cherish being around friends and strangers in real life even more. Are we building to acknowledge that?

I’d love to hear from anyone working in this space/thinking about these things. Feel free to get in touch with me @VirtualElena.

Thank you to Drew, Reggie, and my mom for reading drafts of this, giving suggestions, and sending voice memos <3